I have now seen copies of the books, both hardcover and softcover, and I’m delighted with how they turned out. T-Minus 12 days until everyone else can see it too! (Unless you visit me at TCAF this weekend.)

Bertrand Russell Returns in LOGICOMIX

Torsten reminded me to write a quick note about an upcoming book: Bertrand Russell appeared in my first book, Two-Fisted Science, in a story beautifully illustrated by Colleen Doran. He’s back in LOGICOMIX, by Apostolos Doxiadis, Christos H. Papadimitriou, Alecos Papadatos and Annie Di Donna. It looks excellent — I can’t wait to read it.

T-Minus 25 days until T-Minus!

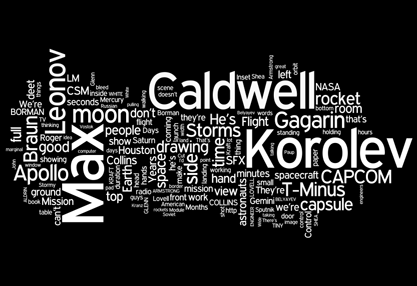

So, enough with the NIH. Here’s the new book, super-condensed via Wordle:

This constellation of words is a map of the script, so it’s all in there (except for the structural stuff like “Panel X” and “Page Y”).

This constellation of words is a map of the script, so it’s all in there (except for the structural stuff like “Panel X” and “Page Y”).

Now you have T-Minus and its director’s cut, all at once, with the main characters looming large! Think of all the time you’ve saved by not having to deal with messy details like story or plot. I’ve even spared you the pictures, so you don’t have to feel sad because the book you’re reading right now doesn’t feature art by Zander Cannon and Kevin Cannon.

But your next book will be chock full of Cannon and Cannon goodness, right?

Right!

Your tax $ at work: The end

These have just gotten longer and longer, haven’t they? If it’s any consolation, the process of reviewing NIH grant applications was longer still, and I couldn’t just mark “All Read” in my RSS feed and walk away once it started. But I’m glad I did it. I’ll close with some random thoughts:

First, if I’d known the National Institutes of Health served Froot Loops® at the continental breakfast I wouldn’t have gone to Whole Foods the night before to get some real fruit™ and a muffin. I don’t think anybody ate the frosted sugar bombs, though, and with almost 50 people in the room nonstop for as many hours as we worked, that’s bordering on a miracle.

I can see how Golden Fleece Awards might come about, since most of the proposals were complex, and most suggested innovative — and thus, somewhat risky — programs. So if you pull out small sections of these things, which you can since line-item accounting is required, you could have made some of the proposals I saw sound quite stupid. But it’s not fair. Watching our NIH overlords (I kid! They were all really nice and helpful) at the meeting, I believe it when they say that their controllers are more diligent than the IRS when it comes to holding people to their promises, and taken as a whole all of the proposals had merit.

In the first third of the meeting, I thought I knew what was going on, in the second third I knew I didn’t, and by the end I was where I wished I’d been at the very outset of the process, months before. So it goes.

One nice thing — everything we read and looked at went into a secure recycling bin, so I went home with less stuff than I arrived. And I finally had a reason to use the “secure empty trash” option to get rid of the electronic versions of the files on my home machine. So, no paper or digital trail, just so you’re not tempted to come knocking.

Shakespeare would have been proud of all the awful puns embedded in the cutesy acronyms serious scientists came up with. In 60+ applications there had to be over 1000 of them, some of them with the same letters meaning different things.

Would I do it again? I don’t know. I don’t think I’m likely to be asked, so it’s probably moot. But all in all, on the NIH scale I’d score the experience 1.2 out 5 (where 1.0 = best). But it’s a difficult and long process for reviewers, and it concludes with two difficult and long days. Not long like a tour of duty in Afghanistan, or a patrol as a beat cop, but it’s a lot of concentrated work with a great deal of responsibility.

As I wrote the last of these notes (in draft form) a mouse took a run at my backpack at National Airport, and then dashed back under the radiator when I made eye contact. In the land of national labs, it was probably a recent escapee from an NIH process as well. Sorry, no Froot Loops® for you, either.

Your tax $ at work: Science jury duty

[Subtitle courtesy of my pal Jane!]

So finally, I went to Washington to meet in secret with my co-conspirators (as assembled by the National Institutes of Health) and decide how to spend one penny of every dollar all my pals in the U.S. sent to the I.R.S. last week.

First, though, a miracle: I don’t think any of the 50 people there so much as coughed more than once or twice. An amazingly healthy crowd, in other words.

And the group that gathered was a smart crowd. As we made introductions, I began to feel like a fish out of…well, not so much water, but out of my solar system. I’m used to traveling in circles where I’m a lightweight, but in this room full of experts I was subatomic. I even botched my intro, but got a laugh anyway — a career path from nuclear engineer to librarian to comic book writer always kills.

The niceties taken care of, we got to work, and started in on hours of careful focus. There was no wireless in the room, and you could see all the fingers twitch with pre-withdrawal syndrome as a result, but our hosts let us know that this was on purpose and done to prevent any attempts at so-called multi-tasking. The NIH has the research to back up the notion that this isn’t possible anyway.

(Sidebar: I’ve read some of it, though not in this context. It turns out you can protest as much as you like, but when it comes to attentiveness the data show that you cannot multi-task when it comes to doing things that require substantial cognitive load. And yes, when I say you, I even mean you. Yeah, I know you’re 14 years old and you’ve blown so much smoke about it that your folks say “Well, kids these days are brought up doing it, so they must be better at it than I am.” Short version: kids fake it better, like veteran barflies can hide that they’ve had 4 beers better than, say, I can. But you can’t beat tens of thousands of years of brain evolution with a few years of simultaneous SMS+Xbox+iTunes+pre-algebra homework. So, we didn’t get wireless access. Your tax $ guaranteed to be at work, at least for the day.)

Anyway, why do I go on about this? Because I thought this meeting would be easy, and thought I had a pretty good idea of what the two days would entail, and thought I was prepared going in. Wrong and wrong and wrong.

Here’s what we had: Over 50 proposals, each ranging from 100 to 300 pages (give or take), each sporting at least 20 acronyms, sometimes using the same letters but meaning different things, and big bucks at stake. Our job was to evaluate the scientific merits of all of them. Our job was to try not to compare them to each other. Our job was to score them on a 1.0 to 5.0 scale. And our job was to do this for each application only after all of us were satisfied that we understood what the proposal would achieve, whether it had the potential to do harm to anyone, and whether it was worth doing.

To cut this down to something that was merely difficult, rather than completely impossible to achieve in 12 hours (more on that later as well), we first went through the proposals and specified which ones we would not discuss in detail and leave unscored (UN). The writers of these UN proposals still get our detailed reviews, and the program managers could still use their discretion to fund any of them based on our reviews and their best judgment. But we wouldn’t discuss these any further. The goal was to mark about half of the proposals UN. We eventually managed this, but it took hours and was difficult because if anyone in the room wanted to score the proposal, they could say so and that was it — it was like we were the security council for the United Nations (UN, get it?) and every member had veto power.

So, 30+ proposals to discuss, and off we went. The primary reviewer summarized the project/program/proposal for the benefit of everyone — realistically, many of us did not read all of the proposals carefully. (I hadn’t.) Then a secondary, tertiary, etc. reviewer added their notes on additional strengths or weaknesses of the proposal, we discussed the protection of human subjects and then the floor opened to questions.

At this point, anybody can ask anything of the reviewers, and everybody did. (Including me, at least by the end. I kept my pie hole shut for most of the meeting, except when I was one of the assigned reviewers.) Nobody ever gave up their opportunity to comment extensively.

We fell behind schedule immediately — each proposal took a minimum of 20 minutes, and most took closer to a half hour. If you do the math and look at the time allotted, we had trouble. And it never got better. The problem? Most of these proposals were good. The investigators wanted to do interesting things, in interesting ways, with promising outcomes for a variety of students in all sorts of settings.

A further difficulty was built into the process because of the reviewers. Mostly scientists, they (and I’ll cop to “we” in this case) have taught themselves to infer things. The problem is, the rules of the game are that you can not infer anything — the proposal writers had to be very explicit about what they would and would not do and we could not assume investigators would pick the more favorable of two methods to do something if they didn’t say which they were leaning towards. Following the do not infer/assume rule proved difficult. So reviewers (not the questioners) had to act almost as lawyer-advocates who worked with the facts at hand, and were cross-examined by the rest of us, and were cross-examined by the witnesses.

I just invoked a legal metaphor, and it would be just as apt to invoke the legislative process. In Congress there are advocates for a law (read: proposal), expert testimony where the experts often disagree, some people are very familiar with a proposal and some not, there’s debate, and everybody votes. There’s even a program executive (read: president) out there that could veto/override our recommendations.

I have no doubt that some bad decisions get made, but the process drove people very effectively towards a consensus. It’s built in, since the reviewers initially give their numerical scores for a proposal and that sets the range the group could use. As a non-reviewer you could go outside that range, but you had to alert the whole group if you planned to do it, and the reviewers were allowed to revise their scores (and thus the range) before the final, individual scoring (read: vote). Again, this drives the group towards consensus, which is both good and bad…good because it forces people to articulate why they disagree with where the group is heading and why they’re leaving the herd, and good because it provides a unified view to the final decision-makers and the people who made the proposal. It’s bad because there’s a subtle pressure (not overt, but it’s herd behavior) to go along and not step outside the pre-set boundaries. All in all, there may be a better way to do this, but with this many applications to deal with, I can’t think of it.

So that’s how it went. The first day we worked from 8am-6:15pm with a one hour lunch break and two 10 minute breaks elsewhen. Then I assume the others were like me and did another hour or so of homework that night, writing up notes and revising evaluations. The second day we started at 7am and went to about 11:15 (ending earlier than we guessed…hurray!). We finished all of the work, which didn’t seem likely when I collapsed into bed that first night.

Next: The end

Your tax $ at work: Book report

Writing evaluations of NIH proposals was where I bonked. I found doing this, and addressing all the critique points (over 50, as you’ll recall from a previous post), difficult and crushing in the way that answering over 50 essay questions about the impact of the French Revolution on post-WWII literature would be. (Open book, so cite your sources; no time limit, but the test is due in 11 days. You may pick up your pencils…now.)

I knew all the words, and understood the premises of the questions. And I knew the goal was to winnow down the applications to a manageable pile for our two-day meeting a few weeks after the critiques were due. But seeing the goal and understanding that it’s a matter of putting one foot in front of the other — or rather, one word after the other — to reach it didn’t make the process any easier.

It took forever, or at least felt like it, and my hourly pay dropped to the level of self-publishing graphic novels about science.

Next: Science jury duty