My latest book isn’t mine, really.

The first name on the cover is E.O. Wilson’s, since Naturalist (on sale Nov. 10, but you can pre-order it now!), is an adaptation of his memoir of the same name. I’d never adapted a book before, and had no idea how to do such a thing when an editor at Island Press asked me to consider it. I think I came clean to Rebecca (hi Rebecca!) about this right away, but she sent me the book anyway. By the time it arrived I was having a hard time stopping myself from underlining passages in a copy I’d already borrowed from the library.

(Hi library! It’s 2020 and I miss visiting you!)

That copy she sent me is now beat up and marked up and I’ve underlined stuff on almost every page. Not surprisingly, the book is visually rich and verbally dense. It wasn’t quite a “choose your own adventure” experience, but there were many pathways through the book to explore in adapting it to comics. But to me, what happened between the lines was just as interesting, and to my mind it was this: Prof. Wilson was talking to us, sure, but he was also talking to himself.

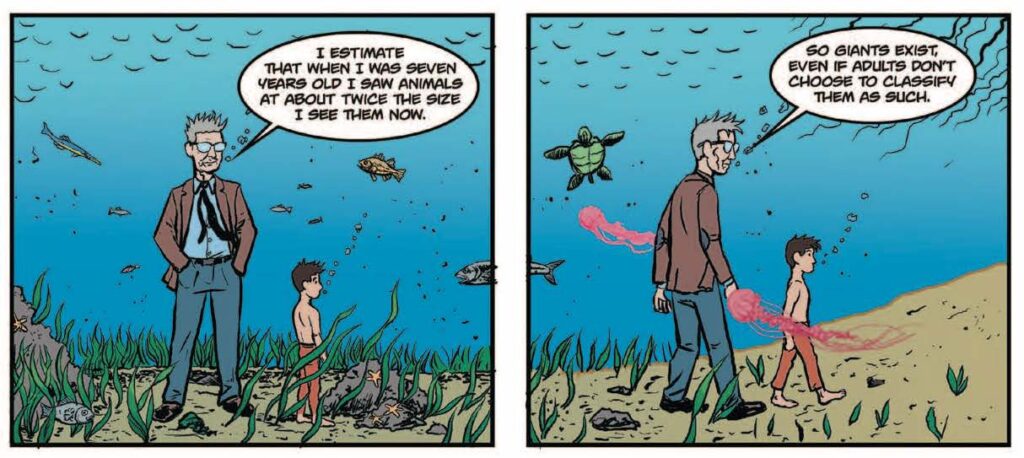

So what does this mean for the comic? It meant, to me, that Wilson should talk to himself in the book. Obviously. But also literally. The present day Wilson — “PDW” in my script — should appear as a character during his early life, and vice versa.

I knew Chris (hi Chris!) was up to the artistic challenge of that, but I had no idea whether Rebecca would buy in, much less Prof. Wilson himself.

(Hi Prof. Wilson; I still can’t bring myself to call you Ed!)

To their credit, though they were skeptical (especially at the script stage, where the story is only words on the page, so it’s all theory…or maybe just hypothesis!) they let me proceed. And once it was reality, and they could see it in the art, they bought in completely. And that’s because comics is so good at keeping readers out of the uncanny valley.

Briefly, the uncanny valley is a phrase from the 1970s introduced by Masahiro Mori, at the time a professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology. He used it to describe how as robots appear more human-like, they become more appealing — but only up to a point. When they get close to human-like, but not close enough, they start to look creepy. That’s when they’re in the valley. There are lots of reasons why 3D animators (think Pixar movies) don’t try to make their characters resemble real humans or animals too perfectly. One of the main ones is they don’t want to trap them, and then the audience, in the uncanny valley.

The comics medium has an advantage here, I think. A somewhat cartoony style, which I prefer over hyper-realistic ones, makes falling into the uncanny valley almost impossible. For one thing, the first image you see of a character fixes the look of that person in your mind, at least in the context of the book. It becomes the baseline for what you expect to see.

That’s not much different from movies, of course, so the real difference is that in comics you’re a reader, not a viewer. And as a reader, you fill in more details — and all the movement and humanity — that happens between the panels. The subtle failures in how light plays over real flesh, or wind moves hair, or the dissonance of hearing a famous actor’s voice coming out of someone else’s mouth? Those can’t happen in comics.

There are valleys and mountains and amazing vistas and wonderful animals of all kinds in our book, of course. It’s about Nature-with-a-capital-N, after all. But I can say that if you agree to accept that first image of E.O. Wilson as The Naturalist, you can trust him, and us, to move you through both space and time and never even approach the uncanny. What you’ll get instead is the wonder and joy of discovery.